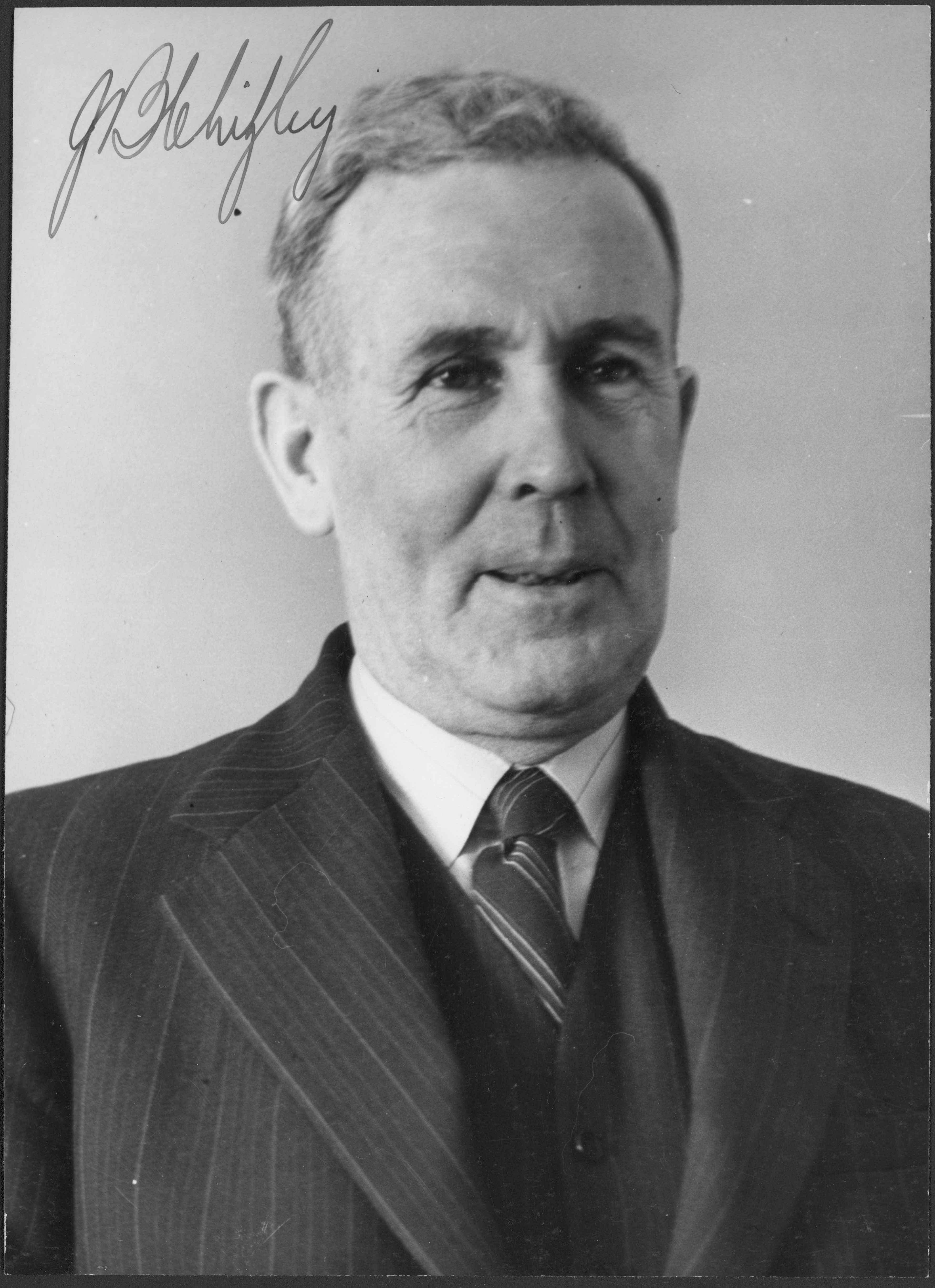

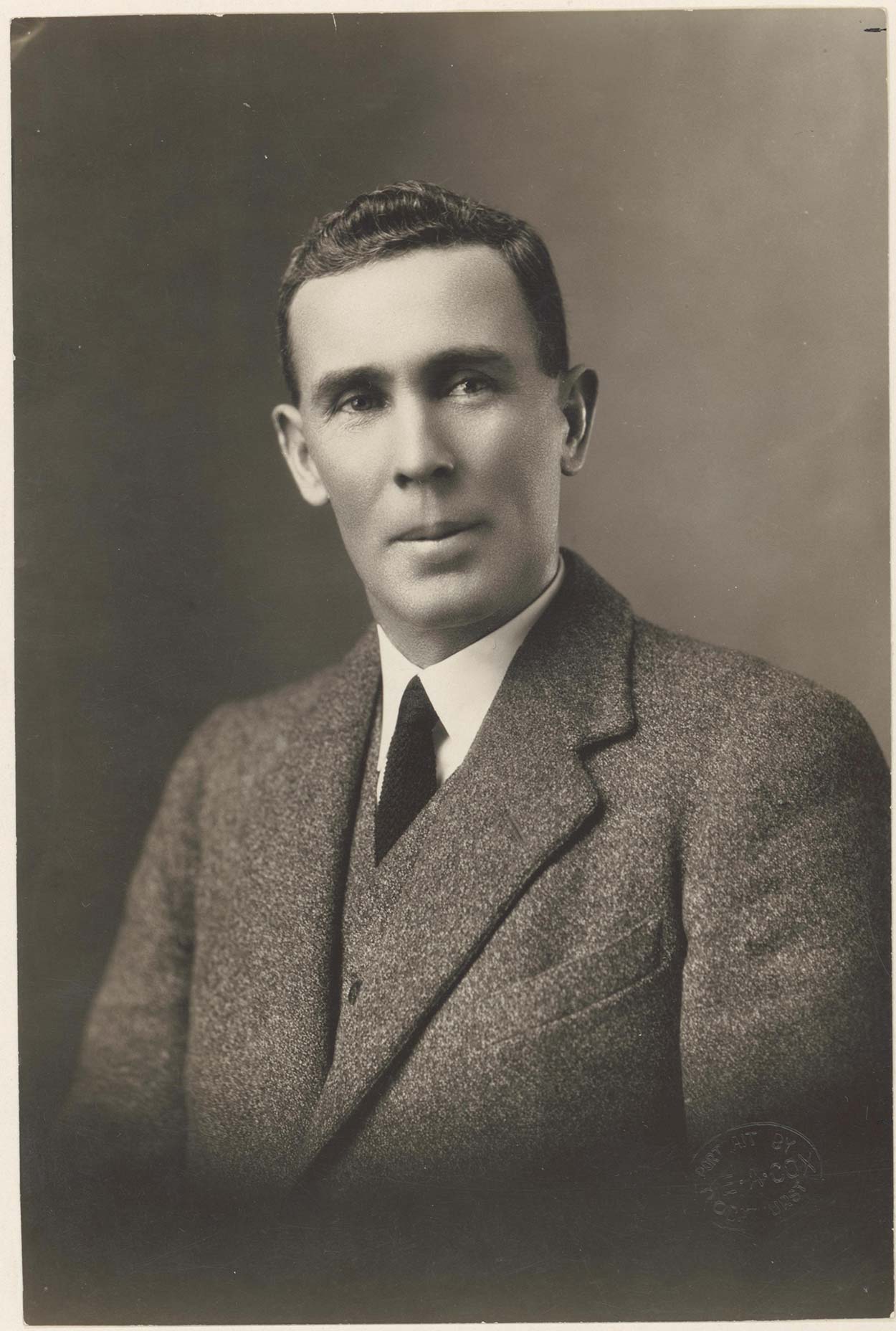

Ben Chifley was one of Australia's most productive treasurers and prime ministers, helping to lead Australia successfully through the Second World War and the challenges of the early post-war years. Yet his path to the prime ministership was far from easy. Chifley was born the son of a Bathurst blacksmith in 1885, and worked for twenty-five years as a labourer and then train driver with the New South Wales railways. But his eyes were always directed towards greater things, and it was clear to those around him that he had the potential to achieve them.

From an early age, Chifley had been imbued by his family with notions of social justice. Perhaps it was due to the Irish background of his grandfather, who had emigrated from famine-struck Tipperary in 1858 and become a farmer growing potatoes for the gold miners eking out a living in the hills around Bathurst. Chifley spent much of his childhood living with his grandfather and only returned to live with his parents and siblings at the age of thirteen, when his grandfather died.

By then, Chifley had had the benefit of the best state school education that the backblocks of Bathurst could provide, which did not amount to much. Nevertheless, it was sufficient to awaken Chifley's enquiring mind and give him a passion for reading. He was also growing up against the background of the 1890s economic depression and the rise of the Labor Party. When all about seemed dark, the party offered hope to ordinary people that they could use their votes and their growing industrial power to achieve economic and social justice.

Chifley achieved a good measure of advancement by his own efforts, rising through the railway ranks from shop boy to engine driver at the age of twenty-six. All the while, he continued to educate himself at night, played rugby with a town team and took a growing part in local branches of the Labor Party and the engine drivers union, In 1912, Chifley defied his Catholic Church by marrying a Presbyterian, Elizabeth Mackenzie, with the couple taking up a residence in a humble two bedroom cottage in Busby Street, overlooking the railway yards.

Like many Australians, Chifley's settled existence was disturbed by the First World War. He joined the movement against conscription in 1916, when Billy Hughes tore the Labor Party and the nation apart in his drive to maximise the Australian contribution to the war. Worse was to come for Chifley in 1917, when a long and bitter strike by railway workers was defeated and he was demoted from his position as engine driver.

The government's harsh treatment convinced Chifley to devote his life to Labor politics by rebuilding the shattered union and later standing for parliament. Although he failed to gain pre-selection for the 1922 State election, he stood as the Labor candidate in the 1925 federal election. The forty-year old railway worker was lauded as having none of 'the claptrap of the professional politician', but he could not succeed in the face of a conservative campaign which told voters they had to choose between the Red Flag and the Union Jack.

Such appeals to fear had less success at the 1928 election, when Chifley was elected with a massive majority. It was a sign of the returning electoral tide for the Labor Party, which came to power the following year under Jim Scullin, only to find itself confronted with the Great Depression. Steering the country through the turmoil was a major test for Scullin and his ministers, who could not agree on how to deal with the crisis and the widespread hardship that it was causing.

Amidst the political furore, and with NSW Labor premier Jack Lang calling for interest payments to British bond-holders to be repudiated, Chifley tried to chart a moderate course through the mayhem. At the same time, he held out the possibility of the government nationalising the banks to solve the crisis. Instead, the Scullin government, with Chifley as Defence Minister, was forced by the banks to accept the so-called Premiers' Plan and implement unpopular cuts to salaries and pensions.

While the consequent restoration of confidence helped to pull Australia slowly out of the Depression, the measures proved to be the undoing of the Labor government, with the party being bitterly divided once more. The NSW branch of the party, controlled by the populist demagogue Jack Lang, was expelled, while Chifley was targeted in his turn by the followers of Lang and expelled from the trade union that he had helped to lead. When Scullin was forced to the polls in December 1931, Labor was soundly defeated and Chifley lost his seat.

Chifley remained cautiously optimistic that Labor would overcome its divisions and that he would again represent the Bathurst electorate. Over the next nine years in the political wilderness, he remained committed to the political process. As president of the NSW branch of the party, Chifley fought to defeat those like Lang who tried to use the cult of personality and populist politics to turn the party in dangerous directions. All the while, he continued to be immersed in the life of the Bathurst region, while at the same time serving on the 1936 Royal Commission into banking. This strengthened his economic credentials for when he would be called to serve as wartime Treasurer in the government of John Curtin.